| Idiot-proof chess help | |

Affiliates Navigation |

The Skewer and the Pin

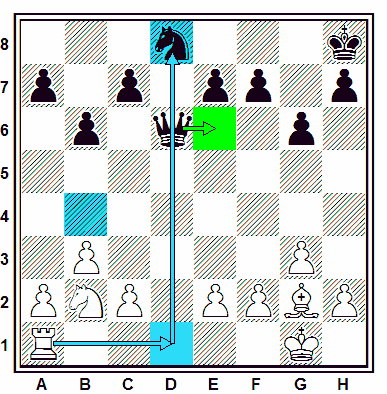

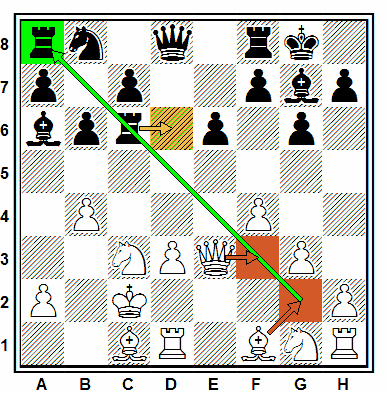

The skewer and the pin are two tactics that are similar enough to cover both in one tutorial. Let's start off with the skewer, shall we? This occurs when a piece comes under attack, and by moving out of the way exposes a piece the same or lesser value to attack. Here is an example of one:  It is White to move, so he can move his a1-rook to d1, attacking the Black Queen. This forces Black to take defensive action and move it from the rook's path; this results in the loss of the knight on d8. (For swimming enthusisasts there is, for some odd reason, a lake on b4, but that's not part of the tutorial) Only bishops, rooks and Queens are able to skewer, as pawns, knights and Kings always move the same distance when capturing. Here is an example of a skewer with either of the two other pieces capable of it:  White could either fianchetto his light-squared bishop or move his Queen to f3 in order to skewer the two black rooks. Should Black move his c6-rook, White is free to capture its brother on a8. Or is he? There are several ways out of a skewer. Here are a few examples:

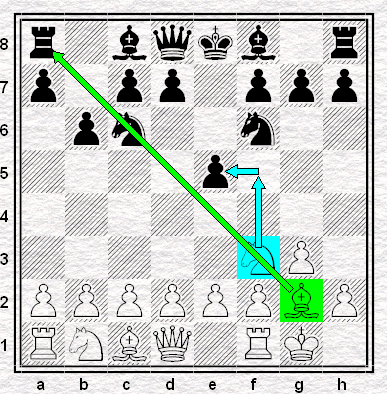

The pin is another trick that only rooks, bishops and Queens are capable of, and it can be seen as a skewer in reverse: it occurs when a pawn or piece comes under attack, but would expose a more valuable piece to attack if it moved. Here's the pin in action:  If White uses his f3-knight to capture the e5-pawn, Black cannot recapture the knight with his own steed on c6 as it is pinned to the a8-rook. In other words, should this knight move, White's bishop will capture the rook on a8, as it becomes exposed. This means the c6-knight is going nowhere fast. Or is it? There are several ways to escape a pin. Better still, some of these are the same ones that work for skewers. These and the others are listed below:

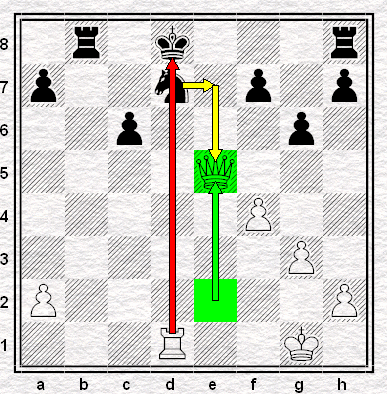

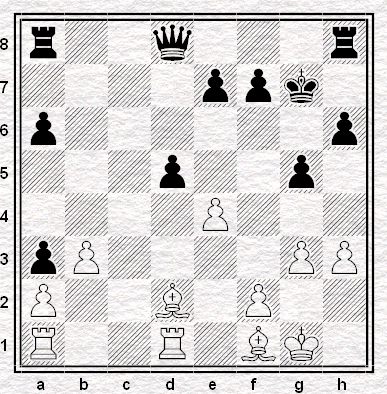

It is also worth noting that there are two types of pin: the type shown in the diagram above is known as a relative pin, because the knight can legally move away (although it's not advisable to do so because of the threat to the rook). An absolute pin occurs when a pawn or piece is pinned to a King, and therefore can't move out of the line of fire, as this would expose the King to check. Below is an example of an absolute pin:  White forks the two black rooks with the move 1. Qe5. Black would love to capture this Queen with 1...Nxe5, but he cannot do so as the white rook on d1 is pinning the black knight to its King! You now know the basics of pins and skewers, so you may wish to try out this problem:  White is down a pawn, but it's his move. Can he take a pawn back on this move, and why or why not? Back to Tactics © 2004-2020 Chess Resources King. All rights reserved. |